We are delighted to have Celine Josephine Giese, a 4th year psychology student from the University of Stirling, on placement with us. As part of her placement she has to write a series of blogs which she has kindly shared with us. This is the first in the series.

Talking Mats is a social enterprise, that has developed a unique communication system that aspires to improve quality of life for people who struggle to communicate effectively, such as people with a learning disability or a stroke as well as people who have dementia. People who are affected by communication barriers have difficulty articulating their needs, emotions and wishes, which can be particularly challenging for carers and clinical practitioners.

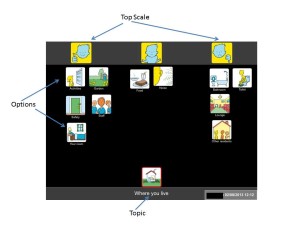

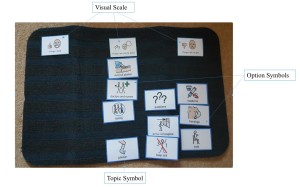

The interactive communication tool consists of an actual doormat and different sets of communication symbols that are placed on the Talking Mat. The communication symbols represent a scale from positive, medium to negative. Specifically, designed topical image sets are used to communicate how the person feels about activities, eating, support and so forth. In addition, they also developed a digital app version.Talking Mats simplifies the communication process by breaking down information into small manageable chunks without the need for literacy. A range of training courses are offered to help individuals to use Talking Mats effectively.

The first day I arrived I was excited as I have not worked in an office environment before. In advance of the meeting I read a lot about their concept and ongoing projects to demonstrate my enthusiasm and interest. I was introduced to the team, who were all very kind and welcoming. During the first meeting, I was introduced to their communication system via a Talking Mat with a general interests’ topic to get to know me better. This was a great way to understand and see how their system works in action. We also filled out the placement agreement and discussed the project I will be involved in.

My role involves supporting Talking Mats in the analysis and impact of the training. For this I am looking at recorded Talking Mat outcome stories from trainees as part of a large-scale project in London Health Authority. I am recording specific details of the stories in an excel spreadsheet, such as the outcome for the patients which will aid the further development of Talking Mats and give feedback to the funders on their investment. Moreover, this analysis will shed light on the bigger impact Talking Mats has on the communication between patients and their carers.

The analysis will be useful in determining the impact Talking mat has on the person whose mat it is and on who used the mat i.e. the interviewer. In addition, it will provide evidence to the organisation of the effectiveness of using Talking Mats. My involvement in the thematic analysis will allow me to further develop excel skills and experience an office setting in a social enterprise, while expanding my knowledge on its origins, current use and future direction potential. Because the cases disclose patients’ personal details I have signed a confidentiality agreement. I look forward to learning more and contributing to the project as well as working with the team. The atmosphere is both pleasant and inspirational and I admire the concept of the enterprise and I feel privileged to be part of such a life changing organisation.Celine’s second blog will be posted soon.

Many thanks to Greg Cigan for this great blog about his study that explored how children and young people with an intellectual disability feel about undergoing clinical procedures.

A clinical procedure is any activity performed by a healthcare practitioner to diagnose, monitor and/or treat an illness such as blood pressure testing, x-rays and other scans (Cigan et al., 2016). While some procedures cause no pain or only mild discomfort when completed, others can be prolonged and potentially painful (Coyne and Scott, 2014). Children and young people with an intellectual disability are more likely to develop physical illnesses including epilepsy and digestive disorders than the general population and can be frequently required to undergo healthcare procedures (Emerson et al., 2011; Short and Calder, 2013). Yet, there is currently little empirical research reporting how children and young people with an intellectual disability experience procedures (Peninsula Cerebra Research Unit, 2016). More research is required so that healthcare services can better understand the needs of children and young people with an intellectual disability (Oulton et al., 2016). As part of my doctoral studies at Edge Hill University, I am conducting a study that explores how children and young people with an intellectual disability experience having a clinical procedure.

From the outset of the study, I felt it was important to obtain data directly from children and young people rather than relying on parents and carers to speak on their behalf. I was keen to adopt methods during interviews that would enable as many children and young people as possible to take part, including those who find verbal communication challenging. After researching different methods, I chose to utilise Talking Mats as the innovative design of the tool offered children and young people the option to express their views entirely non-verbally should they wish to by arranging symbol cards. To date, I have interviewed 11 children and young people about their experiences of undergoing procedures. Each participant was between 7-15 years of age at the time of the interview and had a mild to moderate intellectual disability.

Prior to an interview beginning, I spent time describing and showing each child/young person a Talking Mat and asked whether they would like to use the tool during their interview. Out of the 11 children and young people I have interviewed, three used a Talking Mat. Those that chose not to use the tool were older children who were confident having a verbal conversation with me or those who had a visual disability and could not see the symbols. In all cases, the decision of the child/young person in relation to using the Talking Mats was respected.

The three children who used the Talking Mats were able to express their views non-verbally and also seemed to convey more information than some of those who chose not to use the tool. Viewing the symbol cards within a Talking Mat appeared to help children and young people break down information into smaller chunks which then made it easier for them to process and discuss. Indeed, using a Talking Mat led all three children to discuss information that was new to their parents who sat in while s/he was being interviewed. An example of a completed Talking Mat is shown below which was created by an 11-year-old boy during his interview. The boy clearly expressed that he did not enjoy his experience of having a clinical procedure.

Within my study, I feel using Talking Mats has helped to augment the verbal communication of some of the children and young people which in turn enabled them to take part in interviews and share their views and experiences of procedures. Talking Mats are a valuable tool for researchers working within the field of intellectual disabilities. If used more widely, Talking Mats has the potential to enable more children and young people with intellectual disabilities to have the opportunity to be involved and express their views within healthcare research.

Reference List

CIGAN, G., BRAY, L., JACK, B. A. and KAEHNE, A., 2016. “It Was Kind of Scary”: The Experiences of Children and Young People with an Intellectual Disability of Undergoing Clinical Procedures in Healthcare Settings. Poster Presented at the 16th Seattle Club Conference (Awarded Best Poster Prize), 12-13 December. Glasgow: Glasgow Caledonian University.

COYNE, I. and SCOTT, P., 2014. Alternatives to Restraining Children for Clinical Procedures. Nursing Children and Young People, 26(2), pp. 22-27.

EMERSON, E., BAINES, S., ALLERTON, L. and WELCH, V., 2011. Health Inequalities and People with Learning Disabilities in the UK: 2011. Lancaster: Improving Health and Lives: Learning Disabilities Observatory.

PENINSULA CEREBRA RESEARCH UNIT, 2016. What’s the Evidence? Reducing Distress & Improving Cooperation with Invasive Medical Procedures for Children with Neurodisability. Exeter: University of Exeter.

SHORT, J. A. and CALDER, A., 2013. Anaesthesia for Children with Special Needs, Including Autistic Spectrum Disorder. Continuing Education in Anaesthesia, Critical Care & Pain, 13(4), pp. 107-112.

If you would like more information about Greg’s work you can contact him at Cigang@edgehill.ac.uk

We are very grateful to Lauren Pettit and her colleagues from Pretoria, South Africa for sending us their published paper on a recent research project which used Talking Mats as a research method.

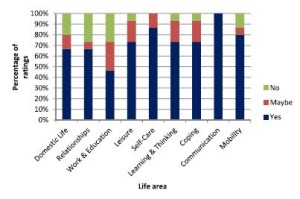

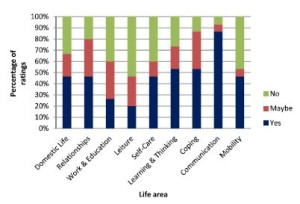

The study’s aim was to describe and compare the views of adults with aphasia, their significant others and their speech and language pathologists regarding the importance of nine life areas for the rehabilitation of adults with aphasia.

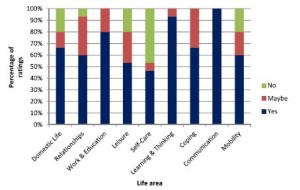

They used Talking Mats to support 15 adults with expressive aphasia to rate 9 life areas in terms of importance to them. The 9 life areas they included were Domestic Life, Relationships, Work and Education, Leisure, Self-care, Learning and Thinking, Coping, Communication and Mobility. These are taken from the World Health Organisation International Classification of Functioning Disability and Health (WHO-ICF). The researchers also obtained the ratings of 15 significant others and the 15 speech and language pathologists treating them.

They found that most life areas were rated as important to work on in rehabilitation by most participants. However, there were some discrepancies between the views of the adults with aphasia and the other 2 groups in the study and significant discrepancies were noted for 3 of the 9 life areas.

The graphs below show the comparisons of the 3 groups of participants. Click on graphs to enlarge

The researchers suggest that ‘These life areas can provide the ‘common language’ for team members to engage in dialogue and identify problem areas related to the daily life functioning of people with expressive aphasia. By simplifying some of the labels of the activities and participation dimensions of the WHO-ICF and pairing these labels with pictures and the interactive Talking Mats interview procedure, adults with expressive aphasia (who often have difficulty participating in the selection of rehabilitation priorities) were able to express their own views. This may be a first step in assisting the adult with aphasia to advocate for themselves and to exercise their right to identify the activities and participation opportunities which they would like to access, and to set rehabilitation priorities based on their choice. While the overlap in priorities among the three groups as found in this study is encouraging, the presence of some significant differences underlines the importance of the voice of adults with aphasia themselves. This ensures truly client-centred rehabilitation that underscores the principles of human rights and a focus on competence rather than deficits’.

To link to the full article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10749357.2016.1207148aphasia

Please contact info@talkingmats if you would like to discuss using Talking Mats in research

Thanks to Agnes Turnpenny for her guest blog on her research on views of people moving form institutional care in Hungary.

There are approximately 15 thousand adults and children with learning disabilities living in large institutions in Hungary. The average size of these facilities is over 100 places, and living conditions as well as the quality of care are often very poor. The Hungarian Government adopted a strategy in 2010 to close and replace these institutions with smaller scale housing in the community. Between 2012 and 2016 six institutions closed and more than 600 people moved to new accommodation. The Mental Health Initiative of the Open Society Institute and the Hungarian Civil Liberties Union commissioned a study to analyse the experiences of the deinstitutionalisation process and as part of this research we carried out some interviews to explore the views of people moving out of the institutions.

The participants – five men and four women – came from one institution in the North East of Hungary, they all had mild learning disability and some had additional mental health issues. Originally the study intended to explore the experience of moving out but due to delays in the project this was not possible. Instead, we decided to examine the expectations of moving from an institution to a smaller home that allows more independence and personalised support. Although only one of the participants had communication difficulties – thus conventional interview methods could have been utilised – I decided to use Talking Mats in order to help participants to contrast their current situation with expectations about the future.

I selected the ‘Where you live’ topic from the Social Care package with some additional images from the ‘Leisure and Environment’ and ‘Relationship’ topics. (The English labels were covered over with a Hungarian translation as most of the participants could read). The question I asked was “How do you feel about these aspects in the institution?” and “What do you think they will be like in the new home?”. (I forgot to take a mat with us, therefore we had to lay out cards on the table.)

It emerged – unsurprisingly – from the interviews that most participants anticipated the improvement of their living conditions from the move, especially better facilities (mainly bathroom and kitchen). Some also expected other positive changes, particularly less conflict with other residents, less noise and better safety –commenting on the prevalence of theft in the institution. There were also many uncertainties; people said they were unsure about how they would get on with their new housemates, how the new support arrangements with staff would work, whether the neighbours will be welcoming etc. The photos illustrate some these issues.

Overall, Talking Mats proved to be a very useful tool in interviewing participants, who really engaged with the method. The images and the completed mats encouraged further comments and explanations on issues that participants considered important with minimum prompting. The drawings were easily recognised and appropriate in the Hungarian context without any adaptations other than the labels. Finally, I felt that the use of Talking Mats in this particular situation helped to overcome some of the power imbalance between the researcher and the participants by giving them more control when handing over the images.

We are really grateful to Agnes Turnpenny from The Tizard Centre University of Kent for sharing her experience . We really value our European work and European connections.

One of the issues which has emerged from previous Talking Mats and dementia projects is that many people with dementia experience difficulties with mealtimes and that it can affect people at any stage of dementia.

Mealtimes involve two of our most fundamental human needs, the basic physiological requirements for food and drink and interpersonal involvement. Mealtimes are particularly important for people with dementia as they may develop difficulties both with eating as a source of nourishment and with the social aspects of mealtimes.

In 2015 Joan Murphy and James McKillop carried out a project, funded by the Miss EC Hendry Charitable Trust, to gather information from the first-hand experience of people with dementia about their views about mealtimes. We ran three focus groups and used the Talking Mats Eating and Drinking Resource to allow participants to reflect, express and share their views.

Findings:

The people who took part in this study felt that there were significant changes in their eating and drinking since their diagnosis of dementia. For some, their experience of mealtimes had changed and several said that they now skip breakfast and sometimes lunch. For some this seemed to be related to forgetting to eat and drink, for others it related to changes in taste whereas for others these meals seemed to be simply less important. Forgetting to eat was particularly noted by the participants with dementia and confirmed by their spouses.

The social aspect of eating and drinking also changed for many of the participants and, given the importance of social engagement for quality of life it is important to be aware of the effects of changes in eating and drinking on mealtime dynamics. For some it may be that they are now less interested in the social aspect of eating with others at home. Others found it hard to eat out because of distractions and lack of familiarity while some felt embarrassed about eating out in front of strangers. Others still really enjoyed going out for meals but added that they preferred to go somewhere well-known to them. The shared mealtime may be a particularly crucial opportunity for social engagement as it plays a central role in our daily lives. Social relationships are central for not only enhancing quality of life, but also for preventing ill health and decreasing mortality (Maher, 2013).

Almost all the participants talked about how their taste had changed both for food and drink which in turn affected their appetite. Some families had overcome the problem of lack of taste by going for more strongly flavoured food. When asked specifically about drinking, thirst was noted as a significant change since diagnosis

Their feelings about the texture of food did not appear to have changed significantly and was simply a matter of preference.

Three additional health issues which the participants felt were connected with eating and drinking were poorer energy levels than before their diagnosis, reduction in ability to concentrate and changes in sleep patterns.

For a copy of the full report please click here Dementia and Mealtimes – final report 2015

The transition from children’s to adult health services for young people with exceptional needs and their families is complex, multifaceted and fraught with concerns and fears. CEN Scotland commissioned Talking Mats to carry out a study to collect the views of 10 young people and their families who are experiencing this transition in Scotland.

The families in the project have given us clear views about their problems and fears and also some thoughtful suggestions for what could be made better. It is often in making small changes that significant improvement can occur. These suggestions include:

- Courses for parents on transition

- More specialist nurses e.g. transition nurses, acute liaison learning disability nurses

- Start preparing early – at least 2 years

- Transition wards for young people

- Training for doctors and nurses about complex needs

- More respite, not less

- Emotional support for parents

- Longer appointment times

- A hotline to GPs

This study captures the complexity and variation of transition health services for young people with complex health needs from the perspective of both the young person and their parents. Despite the problems and fears we also saw evidence of good practice and suggestions, such as those above, which give hope for the way ahead.

To read the full report, including a moving case study, and direct comments from families, please click here CEN Transition Report

.

What are social care outcomes and how do we measure them? The Adult Social Care Outcomes Toolkit (ASCOT) was developed over a number of years as a way of measuring user views on their social care. The ASCOT has been developed by researchers at PSSRU, University of Kent http://www.pssru.ac.uk/ascot/index.php

There are eight domains of ‘social care-related quality of life’ included in the ASCOT. These include:

- Control over daily life

- Personal cleanliness and comfort

- Food and drink

- Personal safety

- Social participation and involvement

- Occupation

- Accommodation cleanliness and comfort

- Dignity

The measure has been tested with service users from different user groups and there are a number of different versions available, including an easy-read version.

Many people with who have communication difficulties are not able to provide views via interview alone. Talking Mats is a communication tool that can be used with people who have communication difficulties. The mat consists of a set of symbols or pictures that are tailored to the subject you want to talk about.

The ASCOT Talking Mat: Tizard Centre’s Jill Bradshaw with Ann-Marie Towers and Nick Smith (both from PSSRU) have worked with the Talking Mats team at Stirling to develop three ASCOT Talking Mats. These will enable people to give their views on:

- Where I Live. This is a starter mat, designed to introduce people to the approach and for those people who might find more abstract concepts more challenging;

- My Care. People will be supported to give their views about whether aspects of their care are going well or not going well.

- Control over my Care. People will be given tools to think about how much choice they have over different aspects of their care. The second and third mats have options for both basic and more abstract concepts.

The TM version of the ASCOT will enable researchers to investigate user views regarding social care outcomes. By using this more inclusive methodology we will be able to engage with these seldom heard groups. The use of symbols in combination with a structured approach will enable us to represent these participants’ own feelings/perspectives in the research, rather than us having to rely on the views of proxies.

Researchers at the University of Kent will be piloting the ASCOT Talking Mats with people with dementia and people with intellectual and developmental disabilities (learning disabilities).

Jill Bradshaw (Accredited trainer) Lecturer in Learning Disabilities, Tizard Centre, University of Kent

Ann-Marie Towers (Research Fellow) and Nick Smith (Research Officer). PSSRU, University of Kent

Thanks to Lauren Pettit for this thought provoking blog about using Talking Mats in a rehabilitation setting in South Africa to compare goals of adults with aphasia, their Speech and Language Therapists and their significant others.

I am a Speech-Language Therapist in Johannesburg, South Africa and I work in neuro rehabilitation for people who have had a stroke or head injury. Over the past few years, I have been inspired to learn more about implementing communication modes to assist people to participate effectively in various communication interactions.

Talking Mats™ is such a wonderful tool that enables people to communicate so many things, from their needs and desires, to engaging in higher level conversations. I have seen the benefits of this tool used in a rehabilitative setting. I recently completed my dissertation with the Centre for Augmentative and Alternative Communication (CAAC) at the University of Pretoria, in South Africa.

The study included adults with aphasia who were still attending therapy at least 6 months after their stroke and were working on activities and tasks in various therapies, for example: Occupational Therapy, Physiotherapy, Speech-Language Therapy, therapies. I wanted to understand what was important for them to work on in rehabilitation to improve in various areas of life. Some of the adults with aphasia had very little or no speech, others had difficulty expressing themselves and finding the appropriate words to use in a phrase or sentence. Talking Mats™ was therefore used to assist them to rate important life areas. The life areas (activities and participation domains) were identified by the International Classification of Functioning, Health and Disability (ICF). This classification system was created by the World Health Organisation (WHO) and may guide therapy assessment and management. The areas were depicted as symbols with a supplemented written word on each card. These nine cards were: Domestic Life, Relationships, Work and Education, Leisure or Spare time, Self Care, Learning and Thinking, Coping, Communication, and Mobility. The adults with aphasia were asked what was important to them to work on in rehabilitation. The adult with aphasia could place the card under Yes, Maybe or No on the velcro mat and provide a comment if he/she wished or was able to. The Speech-Language Therapists who worked with the adults with aphasia and their significant others (a family member/friend or carer, who knew the person well) were also included in the study. They were asked to identify which areas they thought were important for the adult with aphasia to still work on in therapy.

(Click on graphs to see clearly)

It was very interesting to see varied opinions in the results. Six of the areas received similar ratings from all the participants and Communication was highlighted as an important area to work on by all. There were statistical differences found for the following domains: Work and Education, Leisure or spare time and Self Care. The adults with aphasia wanted to work on Leisure or Spare time and Self Care, however, Work and Education was not important to them to work on in rehabilitation, whereas the Speech-Language Therapists rated Work and Education as important for the adults with aphasia to work on. Significant others did not rate these domains as important.

This study gave a glimpse into how some rehabilitation teams are currently communicating and working together and that very often, the people who have difficulties expressing themselves are perhaps not always given the time and space to understand the therapy plan and identify and communicate their individual therapy needs. This needs to be explored further. Talking Mats™ provided a structure and gave the adults with aphasia a ‘voice’ and the opportunity to engage in this complex communicative interaction. I am in the process of sharing the results from the study with the participants. I have encouraged them to sit together in their teams and identify areas that could currently be focussed on in their therapy. Many participants were eager to discuss the results after the interviews were conducted and were interested in the concept of prioritising their rehabilitation needs. I hope they see their participation in this study as the opportunity to further engage in their rehabilitation needs and that it gives them the confidence to participate more fully in many other areas of their lives that they identified as important.

I would so appreciate your thoughts and input. Please respond to Lauren lolpettit@gmail.com

During a research project funded by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation in 2007, Joan Murphy and Cindy Gray developed the Dementia Communication Difficulties Scale (DCDS) to help identify the communication difficulties that a person with dementia might be having and therefore help carers and staff to understand these difficulties and therefore support the person with dementia. The scale comprises 13 statements that are based on existing definitions of the communication problems commonly experienced by people as dementia progresses (Kempler, 1995; Health Education Board for Scotland, 1996):

In early stage dementia, the person

- may have difficulty coming up with words

- may tend to digress and repeat themselves.

In moderate stage dementia, the person

- may find it hard to understand what is said to them, particularly when being given complex information

- may have difficulty maintaining a conversation topic without losing track

- may use semantically empty words (e.g. thing, stuff) in place of content words

- may be difficult to understand.

In late stage dementia, the person

- may make little sense

- may not be able to understand what is said to them, even when simple language is used

- may often repeat what other people have said to them

- may communicate mainly in non-verbal ways

The DCDS requires a third party who knows the person with dementia well (a paid carer or family member) to assess various aspects of their communication on a 5-option scale. People are asked to circle the option that most closely describes the person in question.

Each DCDS option is assigned a score: for example ‘Never’ = 0, ‘Sometimes’ = 1, ‘Often’ = 2, ‘Always’ or ‘Says too little for me to judge’ = 3. A person’s DCDS rating is obtained by totalling their scores for all 13 statements. DCDS ratings can therefore range from 0-39, with a higher rating indicating a greater degree of communication difficulty.

The following stages of dementia group definitions were produced:

• DCDS ratings between 0 and 10.5 = early stage

• DCDS ratings between 11 and 19.5 = moderate stage

• DCDS rating between 20 and 39= late stage.

The Dementia Communication Difficulties Scale is brief, straightforward and quick to complete, and may therefore provide a highly useful tool for the care staff, clinicians and practitioners involved in assessing the needs of people with dementia.

If you would like a copy of the scale please click here: Dementia Communication Difficulties Scale

References:

Kempler, D. (1995). Language Changes in Dementia of the Alzheimer Type. In R. Lubinski (Ed.), Dementia and Communication, San Diego: Singular Publishing Group.

Health Education Board for Scotland (1996). Coping with Dementia: A Handbook for Carers. HEBS.

The final part of my keynote talk at the AAC Conference in Helsinki last month focused on what we mean by communication effectiveness.

It is important to be able to determine the effectiveness / success of an interaction between two people, whether they are politicians, parent and child, husband and wife….. people using AAC systems or people using their own speech.

When I carried out a literature search of peer reviewed journals for my PhD in 2009 I could find no clear definition of communication effectiveness. Some people thought that effectiveness was synonymous with ‘word intelligibility’ or ‘correct syntax’. Others defined effectiveness in terms of the number of words produced on an AAC device. One publication even suggested that effectiveness was demonstrated by someone taking responsibility for charging their AAC device!

The main focus of all the papers I found, which mentioned communication effectiveness, was on needs and wants and only 3 papers cited social closeness as important (click here to read previous blog).

However, some publications did give useful pointers. Light (1988) emphasised that effective communication depends on 2 way interaction and that the partner is a major factor in the success or failure of communicative interactions. Lund (2006) described adequacy, relevance, promptness and communication sharing as key indicators. Ho et al (2005) highlighted satisfaction – partners’ feeling of how well they communicated during the conversation. Locke (1998) stressed that determining the success of any communication is a subjective undertaking as ‘Communication is not a mathematical formula of phonemes, morphemes and syntax, but rather includes casual conversation such as gossip’.

The Talking Mats team has tried to capture what we believe are the essential factors in determining communication effectiveness. We have produced a simple tool – the Effectiveness Framework of Functional Communication (EFFC) which can be used to chart key factors in an interaction on a 5 point scale and give an overall indication of whether the conversation is effective or not.

We have used the EFFC in several of our research projects and show participants how to use it during our training workshops. In Finland I tried it out with the audience of 200 AAC professionals using 3 video examples of different AAC conversations. The resulting scores were amazingly in agreement suggesting that this is a reliable tool.

For a free download please click here EFFC 2014

We would welcome any comments or questions.

Online training login

Online training login