This week’s guest blog, the first of 2 from the authors (Lois Cameron, Nikky Steiner and Luccia Tullio), describes the development process of a set of symbols aimed at supporting practitioners to reflect on the role of identity within their practice.

Every person has their own unique identity, just like they have their own unique fingerprint.

Identity is about how we see ourselves and how the world sees us.

Background

The Royal College of Speech and Language conference 2021 was titled ‘breaking barriers and building better.’ Professor Harsha Kathard from the University of Cape Town gave the keynote presentation and reflected on the key role understanding identity has in clinical practise, stating that ‘understanding identity is key to inclusion’. Secondly, she stressed that if we want to develop better services and support then ‘Turning the gaze to reflect on our positionality is central to change’ .Ash R et al (2023) in their editorial for the British Medical Journal highlight how interventions normally focus on single categories of social identity and ‘fail to account for the combinations of, or intersections between, the multiple social characteristic that define an individual’s place in society.’ They argue that ‘systems of care may consequently overlook overlapping systems of discrimination and disadvantage and exacerbate and conceal health inequities.’

The Development group

Following feedback from clinicians and people who use Alternative and Augmentative Communication (AAC) a working group was formed in March 2021 to explore the role of identity, diversity, equality and inclusion with in AAC practice.

Communication Matters and AAC networks within the UK advertised the group and 12 people responded. These people came from a range of organisations and had a range of lived experiences of diversity including people who use a communication aid to help them communicate. The work was funded by the Central London Community Health Trust and Talking Mats Ltd facilitated the meetings and the work

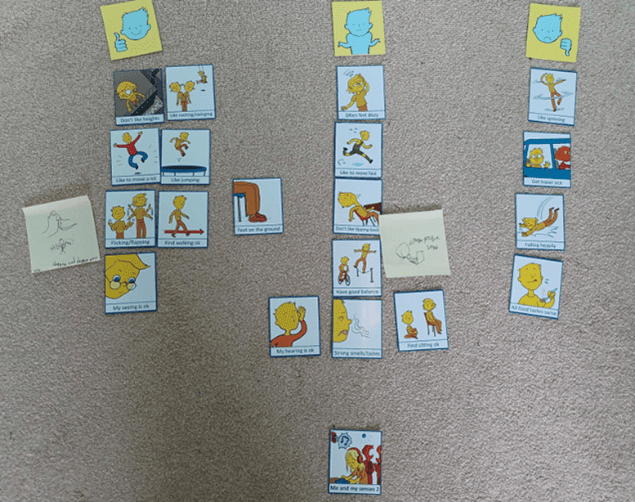

The group worked shaped the resource by reaching a consensus about the components of life that contributed to identity. In the end the group agreed on gender, sexuality, disability, race, neurodiversity, culture, family structure, voice, bilingualism, religion, mental health, personality, politics, intimacy, connecting with others and occupation. The process of developing the symbols was hugely helpful in unpicking what was actually meant by the various aspects e.g. voice. The original image for voice represented accents but the group discussion shaped the image to represent much more so the final image included a rainbow flag, a more general sound wave to represent tone, a Spanish word and an image to represent disability. As one group member said ‘my cerebral palsy is part of my identity. If I am having a voice I want to reflect that identity – I want a cerebral palsy voice’. Identity and the issues surrounding it can be emotive but the focus on the symbols helped contain the emotion and supported group members to listen to the perspective of others.

The whole iterative process of developing the resource and clarifying what the symbols should look like allowed the group to be clear about the individual meanings of abstract topics. This wider understanding was captured in a glossary to go alongside the symbols. For example, Identity has the following definition: Every person has their own unique identity, just like they have their own unique fingerprint. Lots of different characteristics make up our identity. This is what makes us different from other people. Sometimes we may share some of these characteristics with other groups of people, which can also be part of our identity. Identity is about how we see ourselves and how the world sees us.

Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: a visual framework to support the exploration of Identity within practice.

The resource is seen as a support for constructive reflection by practitioners on identity and allows them to consider the different aspects of their patients’ lives that may impact on their interventions. The final Talking Mats symbols have the suggested top scale of ‘I considered a lot’, ‘I considered a bit’, ‘I have not considered yet ‘. It could be used individually or by a team as a group discussion tool.

As the resource uses the Talking Mats framework, it is recommended that practitioners have completed their Talking Mats foundation level training

If you are interested in completing Talking Mats Foundation Training, you can see the training options in our shop here.

References

Kashard H 2021 Keynote breaking barriers and building better The Royal College of Speech and Language conference.

Ash Routen, 1 Helen-Maria Lekas, 2 Julian Harrison, 3 Kamlesh Khunti1,2023 Interesectionality in health equity research BMJ 2003 https://www.bmj.com/content/383/bmj.p2953

Our thanks for this blog go to Olivia Ince, Talking Mats Licenced Trainer and Speech & Language Therapist. This blog post reflects on the use of a Talking Mat with a Thinker called M who speaks English as an additional language. The Listener in this Talking Mat is Jono Thorne who is a colleague of Olivia. Jono did this Talking Mat for his video as part of a Foundation Training course run by Olivia.

M is a young adult who came to the UK as an unaccompanied asylum-seeking child. M is from a country in Central Africa and speaks a language which is not widely spoken outside of the region. Accessing interpreting and translation services in the UK for their native language is very difficult and M has therefore had difficulties learning English. This means the people around M often have difficulties finding out M’s views, which is why Jono thought a Talking Mat could be an invaluable communication tool for M.

M already uses some visual support, for example hand gestures and using objects such as food items when having a conversation in the kitchen. The people around M are unsure what M’s level of comprehension is in English and therefore they make adaptions such as simplifying their language. M’s expressive language in English is typically the use of one- or two-word utterances and yes/no responses.

To see if M would be able to engage with the Talking Mat process, Jono chose a simple topic to start with and one which he knew would interest M: food. The Top Scale used was like/unsure/ don’t like. Jono noted that M quickly understood the concept of the Talking Mat and the visual element seemed to support M’s understanding. The Talking Mat process including the side-by-side listening also facilitated rapport building.

Jono noticed that M was decisive and seemed certain about their placement of the option cards. The Talking Mat helped M to share their views on a larger number of items than would likely have been possible via a verbal conversation. M also joined in with the recap of their Talking Mat as part of the review and reflect by reading out the Option cards with Jono, which meant M was even more involved with the process.

There were a couple of difficulties for M during the Talking Mat process: the blanks and the option to change where the Option cards were placed. Jono tried to explain these steps using simple language but M did not appear to understand these concepts due to their level of comprehension of English. As M had seemed sure of their initial placement of the Option cards and they joined in with the recap, Jono felt that the Talking Mat was an accurate reflection of M’s views that day. Continuing to model these steps to M will likely help them to develop their understanding of these parts of the Talking Mats process over time.

Jono reflected on how useful it was to now know which foods M likes and doesn’t like. He also reflected on the potential future use of Talking Mats with M on more complex topics and to facilitate participation in decision-making now that it’s clear M understands how a Talking Mat works.

If you are interested in completing Talking Mat Foundation Training, you can read more about it here.

Our thanks for this blog go to Deborah Little, Speech and Language Therapist; Clinical Lead for AAC & Total Communication (Children and Young People) NHS Dumfries and Galloway.

“Can we do a Talking Mat today Deborah? This is the question I am asked as soon as I enter the Learning Centre in one of our local schools by an enthusiastic 8 year old who has been exploring what completing a Talking Mat (TM) is all about this term. While we are in the early stage of this school’s TMs journey, the impact of embedding the approach into the fabric of how Children and Young People (CYP) are supported to communicate in school is already proving transformative.

Article 12 of The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) guarantees children the right to express their views and opinions freely in all matters affecting them. The responsibility of ensuring children experience this right is also underlined in NICE guidelines (2022) that state: “Education, health and social care practitioners should always: put the life goals and ambitions and preferences of the disabled child or young person with severe complex needs at the centre of planning and decision making.”

Working with my teaching colleagues within one Additional Support Needs (ASN) setting this year, we reflected on how effectively the CYP were able to give their views and how consistently these views were acted upon in meaningful ways. We felt that this was an area we really wanted to improve upon and specifically we wanted to explore the following key questions in our minds:

- How can we support CYP’s understanding of their right to give their views and opinions? We reflected that for some CYP, their experience of being able to do this was very limited and that their understanding of using a TM was not yet at a stage where they were able to represent their views. We therefore wanted to prioritise finding out what helped these CYP to use TMs with understanding.

- How can we support CYP to know that they can tell us they aren’t happy about something? We reflected that during ‘Emotions Works’ discussion times many of the CYP routinely shared that they felt ‘happy.’ It was rare for the CYP to talk about unhappy feelings. We felt worried that the CYP often gave responses that they felt would be ‘right’ or pleasing to adults.

- How can we ensure we create a culture of prioritising time and space for CYP to share their views, opinions and ideas? We thought about opportunities throughout the school week that would create space and motivation for the CYP to engage with TMs. We wanted to achieve a feeling of TMs being integral to the everyday, as opposed to a sporadic ‘add on.’

To answer these questions, we agreed on the following key change ideas to implement and evaluate:

Developing understanding of the Talking Mats process linked with familiar learning opportunities.

Dynamic Assessment is an approach familiar to those working with CYP who use Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC). Adapting activities dynamically, being responsive to CYP’s progress, allows progressive skill enablement. Together with teaching colleagues, we applied this thinking to helping the children use TMs with understanding. If we had tried having a conversation using TM only a couple of times, our evaluation could have been that TMs wasn’t yet a tool we could use because for example, the CYP were putting all their symbols into the ‘I’m happy with this’ column only. Instead, we thought “OK, that’s where the CYP are now, let’s give them opportunities to practise engaging with this new tool and time to develop using the approach with understanding.” Put another way, we prioritised another key concept within the field of AAC: we Presumed Competence. We believed that the CYP had the ability to share their thoughts, feelings and ideas if we introduced TMs gradually, linking with the activities above, that were tangible and familiar to the thinkers.

Consciously modelling that is OK to have negative feelings and opinions.

When a CYP is learning what might be possible in terms of communicating with AAC, best practise is for supporting adults to model the AAC. This means, adults ‘use AAC to teach AAC.’ We show CYP that we highly value the AAC and want to use it too. We use it in real situations, modelling vocabulary to help CYP understand the symbolic vocabulary and how they can begin to use it too. When helping the CYP understand how TMs could help them express a wider range of emotions, we tried out using this approach. Now and again, supporting adults would share with the CYP how they were feeling about things using TMs and would include negative feelings.

One CYP had a memorable response to my sharing that I was feeling “not happy” with my cat. The CYP’s eyes widened and he became instantly animated, using his AAC to ask “cat..bad..what?” I was able to explain that my cat had been scratching my carpets and I was feeling upset about this. The CYP then used his AAC to say “cat…dig!” He pointed at the ‘not happy’ symbol in the Talking Mats top scale, jointly sharing his attention to this symbol and understanding of what this meant with me. The next week, we used TMs to ask this young person about a social group he had attended. For the first time, we noticed him ‘swithering’ across his top scale while making his choices. Also for the first time, I was confident that he shared his authentic feelings with me. I reflected on the power of modelling and normalising feelings that are ‘not happy.’

So, where are we now? The key themes from our findings after a year of using TMs as described above are:

In summary, using TMs in this setting has all supporting practitioners in agreement that it is not only important to listen to CYP when we know they might be having a tough time; we need to create space to listen all of the time, week to week, with authenticity and without agenda. The principles regularly used within AAC practice of: modelling, presuming competence and dynamic assessment have been effective in supporting more children to be able to experience their UNCRC Article 12 Right, more of the time and with increased understanding and confidence.

References

- UN Convention on the Rights of the Child – UNICEF UK

- NICE Guidelines [NG213] (2022) Disabled Children and Young People up to age 25 with severe complex needs: integrated service delivery and organisation across health, social care and education.

- Emotion Works www.emotionsworks.org.uk

- Daneshfar, S and Moharami, M (2018) Dynamic Assessment in Vygotsky’s Socioculturaly Theory: Origins and Main Concepts. Journal of Language Teaching and Research 9(3):600

- Donnellan, A (1984) The Criterion of the Least Dangerous Assumption. Behavioural Disorders, 9 (2), 141-150

- Sennott, Light and McNaughton (2016) AAC Modelling Intervention Research Review. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilties 41 (2)

Talking Mats is available both as a physical resource and as a digital web-app. In this blog, our Digital Lead, Mark, gives an update on some exciting recent developments on our Digital Talking Mats platform.

It’s been over 2 years since we launched our new Digital Talking Mats platform, and we’re so pleased that more and more of the Talking Mats community continue to discover how it can be used to improve conversations in a wide range of contexts and situations.

We’re always looking for ways to improve the user experience of Digital Talking Mats, and over the last couple of years we have so appreciated the feedback given by Talking Mats customers who have been using the platform.

This feedback has led to plenty of tweaks and updates behind the scenes, but in this blog I want to highlight some updates we have recently implemented, which we hope will improve the experience for those using our digital platform, and also let you know about what upcoming features are in the pipeline.

Grouping and Deleting Thinkers

Users can now create groups/categories for their Thinkers, and organise them in a way that is most helpful for their context. Whether it is school classes, hospital wards, or care homes, for example, users can choose what to name the groups, and how many Thinkers are in each group.

As well as creating Thinker groups, users now have the option to delete any Thinker from their list. This may be a former patient, a Thinker from a previous job, or simply a Thinker that was used to test out the digital platform.

Sharing Personalised Mats

For users who are Talking Mats trained and are part of a Digital Talking Mats Organisational Subscription, we’re excited to say that personalised Mats that have been created can be shared with other members of your organisation. This means that if you work in a specialist department and require a bespoke mat for your context, one member of your department can create a personalised Mat, and share with every member on the subscription.

Upcoming Feature: Private Resources

At Talking Mats, we often do consultancy projects with organisations, to create specialist Resources for specific contexts. Sometimes these Resources end up for sale in our shop, for example, our Funeral Planning, Careers, Work & Employment, and Youth Justice Resources.

In other cases, an organisation may wish to have exclusive access to a Talking Mats Resource produced as part of a consultancy. This is easily achieved with physical resources, but has so far not been possible in the context of the digital platform. With the upcoming private resources feature, we will be able to upload a resource and grant access only to a specific organisation.

At Talking Mats, we are committed to continually developing and improving our digital product for customers. If you have any feedback, or any ideas for improvements we can explore in the future, please get in touch with us at info@talkingmats.com.

If you are interested in Digital Talking Mats for yourself or your organisation, you can read more about the platform here. We have subscriptions available from as little as £5 per month and you can see the available options in our shop here.

Do you work with people with intellectual disabilities and / or autism?

Researchers at the University of Hertfordshire have been working with Talking Mats to develop a range of symbols to help people with intellectual disabilities and/or autism to communicate symptoms of long Covid. It is hoped that these symbols will help facilitate conversations and improve accessibility to long Covid service pathways and improve health outcomes.

There are three topics that have been developed:

- Symptoms – This Topic uses a suggested Top Scale of I have / I sometimes have / I don’t have. Options in this topic include heart going fast , dizziness , brain fog.

- Mood – This Topic uses a suggested Top Scale of This is me / This is sometimes me / This not me. Options in this topic include frustrated, not interested, confident

- Getting Help – This Topic supports you to discuss how supported the individual feels and where their key supports are coming from. A suggested Top Scale is Going well / Unsure / Not going well. Options in this Topic include GP, online/phone support, specialist team.

This Talking Mats resource was developed in partnership with a group of people with intellectual disabilities and people with autism alongside a range of health professionals. People who had lived experience of long Covid were also involved in the group.

Participate and use the resource

We would like to hear from a wider cohort of practitioners working with people who have learning disabilities. For example, nurses, speech and language therapists and occupational therapists. We want to know if there is a need for this long Covid Talking Mats resource. This resource can also be used where long Covid has not been formally diagnosed but you want to listen to the person with a learning disability and hear about their experience of their long-term health condition.

If you would like to participate, and meet the following criteria, we would love to hear from you.

Criteria:

1. Have completed Talking Mats Foundation Training course.

2. Work in a setting supporting people with intellectual disabilities and/or autism.

If you would like to get involved, please complete the following survey by the end of April 2024.

Click here for the Long Covid Survey

Please note that should you consent to be involved in this project, your information will be shared with the University of Hertfordshire.

The team will be looking for feedback by the end of July 2024 and you will be asked to fill in a short survey for each Talking Mat that you complete . This survey will be sent to you alongside the long Covid resource.

If you have any questions about this, please do not hesitate to contact info@talkingmats.com

Our thanks for this guest blog go to Meredith Smith, Paediatric Physiotherapist and Lecturer in Physiotherapy in the School of Allied Health Science and Practice at the University of Adelaide. In this blog, Meredith talks about the development of a Talking Mats resource to facilitate self-reporting in pain assessments for children and young people with cerebral palsy.

Our research team has been working on modifying pain assessment tools so they are more appropriate, relevant and accessible to children and young people with cerebral palsy (CP). People with CP have varying functional, communication and cognitive abilities, which makes existing assessment tools (often pen and paper questionnaires) difficult to use across the spectrum of ability. As a result, children and young people with CP often don’t have the opportunity to self-report how pain is impacting their function.

We are based in Australia and our team is made up of physiotherapists, an occupational therapist, a medical practitioner, researchers and people with lived experience of CP. One of the first things we did as part of this project was to ask people with lived experience of CP and clinicians what we could do to make two specific pain assessment tools more accessible and relevant to people with CP and different abilities. One of the clinicians (a speech pathologist), suggested we consider a Talking Mat alternative for each of the assessment tools. These two assessments focused on two concepts – 1) how pain interferes with function and 2) pain-related fear. We were keen to focus on these assessments as this would help us to not only open up a conversation about pain with children and young people with CP, but would also provide us with a way of identifying children who might benefit from particular pain interventions, and allow us to monitor the effectiveness of these interventions.

Prior to this suggestion I had heard of Talking Mats but never used it. Our research team underwent Talking Mats foundation training which was excellent, and we were all really impressed with the concept and its application in varying contexts. We had initially thought that we might need a Talking Mat to get feedback from children on the assessment tools, but we all agreed that converting the pain assessment itself into a Talking Mat would make the most sense for now.

Working with the Talking Mats team was a fantastic experience. We all really appreciated the expertise of the consultants in considering how we worded some of the assessment tool items. The symbols created were also excellent, and when we tested them with children and young people with CP they were simple and easy to understand.

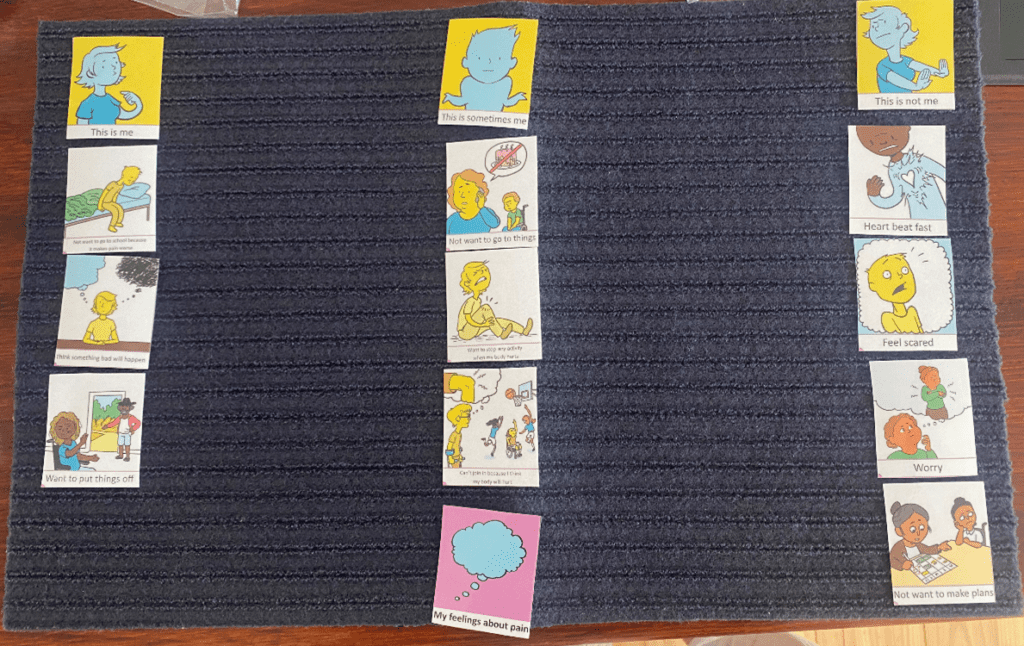

Here is an example of a Talking Mat discussing pain interference with function. The lead in phrase is ‘how much does pain get in the way of……’. This Talking Mat was easily understood by most children with CP, even those with moderate cognitive impairment and complex communication needs.

The second Talking Mat looked at pain related fear, with the lead in phrase ‘pain makes me……’. This was a more challenging and abstract concept, but was much easier to explore using the mat than on a standard pen and paper questionnaire. The Talking Mat versions can be interpreted as a 5-point response scale (the three response options and then two in-between sections), allowing us to still total an overall score for the assessment.

The feedback from children, young people and their families has been very positive. Families of children with cognitive impairment or complex communication needs have shared with us that previously it was assumed that their child could not self-report pain, and often they were asked to proxy-report on their behalf. Parents have told us how difficult it is to proxy-report on personal concepts such as pain-related fear, and that they couldn’t possibly know for certain how pain was making their child feel.

We are in the process of continuing to test the Talking Mats resource and look forward to making the it more widely available in the future.

Keep an eye on our website for more information about the Pain Assessment Resource as this project progresses.

If you are interested in completing Talking Mats Foundation Training, you can find out more here.

When this blog from Janie Scott, a Talking Mats Licenced Trainer with Perth and Kinross Council came in I was a bit stumped. There was a lot that I wanted to highlight but I didn’t want to focus on one thing and detract from others:

- The importance of understanding and applying the Talking Mats framework allowing conversations on topics not covered by our resources.

- Demonstrating how Talking Mats can enable the voice of the child to be heard, upholding Scotland’s Promise to care experienced children, young people, and families.

- A model for embedding Talking Mats in a service.

I decided to go with everything. In 2 parts.

Part 1

Talking Mats; UNCRC, the Promise and hearing the thinker:

Janie Scott, (Highly Specialist SLT Perth & Kinross Council)

Scotland is currently progressing with the incorporation of the United Nations Conventions on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) through the UNCRC (Incorporation) (Scotland) Bill.1 The UNCRC, article 12, states that, ‘children have the right to give their opinions freely on issues that affect them. Adults should listen and take children seriously.’

Talking Mats enables rights-based participation for children, allowing them to form and express views freely. It allows others to understand the issues and, as stated above, have those views taken seriously 2

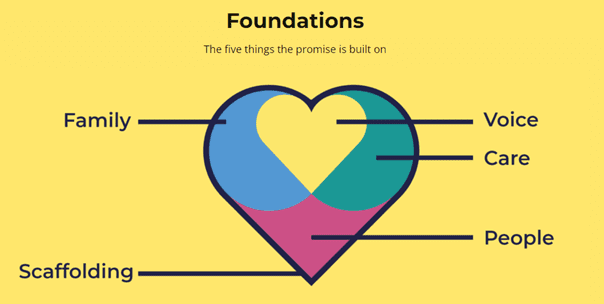

The ‘voice’ of the child is central to The Promise3. Talking mats should be considered the ‘scaffolding’ to enable a voice to be heard.

Last year I rolled out Talking Mats foundation training to Social Workers and Senior Social Care Officers working within Services for Children, Young People and Families, in Perth and Kinross Council. Fundamental to Talking Mats is the framework; the ability to use an appropriate top scale, open questions, silence and pass control to the thinker. Having demonstrated the importance of the framework in the training, we then went on to develop symbol sets specifically related to the work of the Social Work teams. These covered a wide range of topics including:

- sleep

- becoming a foster family

- contraception

- sexual knowledge

- contact arrangements,

- behaviours that adopted children think might be difficult to deal with

- grief

- school life

- triggers (related to drugs and alcohol)

I was privileged to hear several reports of how Talking Mats had allowed the voice of the children and young people to be heard which had a direct positive impact on their lives. Here are two powerful examples from a parent and a social worker.

Parent

” I have really enjoyed using Talking Mats. It lets me see everything in an organised way. I really like that. It has also shown me the progress I have made; I have found using an advocate really useful in the past but I don’t need to use an advocate any more as I feel more confident. I used to struggle with making decisions but this mat made me realise that I make decisions all the time and they are not wrong decisions.”

Assessing Social Worker for Kinship Care

“As part of my role, I need to find out information from teenagers on how they feel their kinship placement is going. Typically I find that many teenagers give one word answers or sometimes they tell me what they think I want to hear. Talking Mats has been useful in my work in allowing teenagers to open up. It has also been useful with children who have English as an additional language. The children did speak English, but it made it easier to get their ‘story’ from them.

“There was one particularly quiet and reserved teenage boy who was reluctant to share information. The Talking Mat allowed him to tell me much more than when I had initially questioned him. Through the Mats we were able to distinguish the difference he felt between living at home and living with his kinship carers. The Talking Mat enabled him to express that his kinship carers were open to having discussions with him and talking about his worries whereas his Mum did not want to talk about his worries. this was something that I was able to support him in sharing with his Mum as part of the plan for him to return home.“

To uphold Article 12 services must be proactive in creating opportunities to listen to the voice of the child. Talking Mats is enabling the voices of children, young people and families to be heard in Perth and Kinross. This voice is influencing key decisions in their lives across a variety of forums including the Children’s Hearing System, Kinship Panels, and Child’s Plan Meetings.

- Children’s rights legislation in Scotland: quick reference guide – gov.scot (www.gov.scot) ↩︎

- Can Scotland be Brave – Incorporating UNCRC Article 12 in practice – gov.scot (www.gov.scot) ↩︎

- Foundations of the promise – The Promise ↩︎

Talking Mats Director, Margo MacKay, will be presenting with Laura Lundy, Professor of International Children’s Rights, QU, Belfast on Wednesday 1st of November, 2023 at NHS Education Scotland webinar; ‘The voice of the infant and child; rights- based participation for children and young people’

For more details please see the NES website.

Read ‘Can Scotland Be Brave, Incorporating UNCRC Article 12 in practice here

Thank you to Lisa Chapman,Lead Speech and Language Therapist at Bee U: Child & Adolescent Mental Health Services, Midlands Partnership NHS Foundation Trust, who has shared her thoughts about the new sensory resource, sharing what it means to her both professionally and personally. Use these links to read more about the resource and our giveaway offer and to book directly.

A personal and professional journey intertwined.

Communication has always been one of my passions. As a languages teacher I was struck by the speech, language and communication needs (SLCN) of my students and this led me to retrain as a Speech and Language Therapist (SLT). As a parent I saw how my youngest son struggled to communicate his needs and how others struggled to understand him across different environments. He now has a diagnosis of Autism and the experiences we have had together were the start of my journey to explore Sensory Processing.

Sensory Processing, Sensory Integration and Neurodiversity.

Sensory processing is something we all do, it is how we make sense of the world around us using our 8 senses. These websites offer a good general overview of our senses and sensory processing;

- Understanding Sensory Processing and Integration in Children (sensoryintegrationeducation.com)

- Free online sensory processing course for teachers, assistants and parents (griffinot.com)

How this information is then dealt with is referred to as ‘Sensory Integration’; ‘the processing, integration and organisation of sensory information from the body and the environment’ (Schaaf & Mailloux, 2015, p5).

From my growing personal interest came ideas on how sensory processing and integration overlapped with my professional life as an SLT. Hooked, I enrolled on the Sensory Integration Masters course with Ulster and latterly Sheffield Hallam University. I completed my Diploma in 2021 and hope to complete my Masters dissertation later this year.

I love that I have been able to weave my ‘lived’ experiences into my professional development. These experiences continue to overlap. Most recently, this has involved exploring the concept of Neurodiversity, “the infinite variation in neurocognitive functioning within our species” (Walker, 2014a). Walker clarifies that the neurodiversity paradigm has three fundamental principles

• Neurodiversity is natural and valuable. We are stronger because of our diversity.

• There is no one ‘right’ way to process information. There is no such thing as a ‘normal’ brain.

• It is important to acknowledge social power dynamics exist in relationship to diversity. Walker (2014b) reminds us to ‘check’ our privilege. This will frequently involve moving out of our comfort zone (Murphy, 2022).

This paradigm has become a core framework for me as both an SLT and a parent. It helps me make sense of variations in communication and sensory experience, to reframe these as differences, not deficits. Understanding my son’s sensory processing has helped me see the world through his eyes allowing new spaces for communication and different conversations. It has helped to reduce the Double Empathy gap (Milton, 2012).

I am equally aware of the impact of environments. Luke Beardon’s (2017) ‘golden equation’, one I quote often, aptly summarises this. “Autism + Environment = Outcome”. Environment here includes identity, the sensory environment, other people and society (Beardon, 2022). The value of having a clearer understanding of your identity and needs is also context dependent, ‘relational’ (Chapman, 2021). You, and others around you, may have great insight into how your body and mind work, but this can only go so far. If no one is listening to you, and environments in their broadest terms are set up to be against you, are ‘low-functioning’ (Patten, 2022, p.8), it is harder to achieve positive and authentic outcomes.

For my autistic son, education settings have sadly often been ‘low-functioning’ environments, placing an immense toll on his sensory processing, communication and ultimately on his emotional well-being. The impact on us as parents has been no less challenging, coping with multiple exclusions from multiple placements. I have equally seen the power of restorative, ‘high-functioning’ environments (Patten, 2022, p.12) that enable him to be the best he can be: environments that offer success, building on his interests and abilities.

The very nature of neurodiversity suggests that we all process sensory information differently. A better understanding of individual sensory experiences gives more information that we can use to create and advocate for ‘high functioning’ environments for everyone, and achieve equity. A crucial first step in neurodiversity affirming practice is respecting an individual’s ‘epistemic authority’ (Chapman & Botha, 2022). To listen without prejudice, and not to enforce that we know best, just because of our position.

With this as my personal and professional ‘framework’ I welcomed the opportunity to trial the Talking Mats resource; Me and My Senses and my final thoughts are around using it with my son.

My personal journey continues; learning and growing

As his mum, and as an informed professional, I felt that I already knew my son’s sensory profile, that I could predict what some of his answers were going to be. He had also already had a full OT-ASI assessment. I came to this as an exercise in ironing out snags, not primarily one of personal learning. I couldn’t have been more surprised by the wealth of new information I came away with, after using the mat with him.

My most important learning was around the significance of smell for my son. Using the mat gave him the space and opportunity to share his insights into smell that I had never really appreciated before. What’s more, this ‘opening up’ extended beyond the time we were using the mat. For the rest of the day he continued to refer to his mat, adding further examples and anecdotes about ‘smell’ as a fundamental sense for his well-being. The mat had provided a safe space for exploration, connection and communication beyond its physical presence. It was a humbling, but also precious experience. It illustrated beyond doubt the importance of listening, but also the immense privilege of opening up and sharing a space that facilitated my son’s voice to be heard.

Until now, few tools have captured the lived ‘sensory’ experiences of children and young people. The Talking Mats ‘Me and My Senses Resource’ meets this need. It places an individual’s voice as central, acknowledging and facilitating autonomy and agency. As such, it is an invaluable tool to anyone wishing to explore sensory processing in a neurodiversity affirming way.

References

Beardon, L., (2017, July). How can unhappy autistic children be supported to become happy autistic adults? https://blogs.shu.ac.uk/autism/files/2017/07/How-can-unhappy-autistic-children-be-supported.pptx

Beardon, L. [@SheffieldLuke]. (2022, December 11). Autism + environment = outcome; environment could include: autistic self (e.g. understanding of self); others in that environment; the sensory. [Tweet]. Twitter. https://twitter.com/SheffieldLuke/status/1601894447721111552?s=20&t=HmyywdI4gDSrDJ1BggtF3w

Chapman, R. (2021). Neurodiversity and the Social Ecology of Mental Functions. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 16(6), 1360–1372. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691620959833

Chapman, R., & Botha, M. (2022). Neurodivergence-informed therapy. Developmental Medicine Child Neurololgy. 00: 1– 8. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmcn.15384

Milton, D. E. M. (2012). On the ontological status of autism: The “double empathy problem”. Disability & Society, 27(6), 883-887. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2012.710008.

Murphy, K. (2022). Neurodiversity in the Early Years. Neurodiversity & ableism reflection tool. https://assets-global.website-files.com/5f903cbab2ae71f26cf02400/638a04bcc5a15c6fda2c02b1_AUDIT_Kerry%20Murphy.pdf

Patten, K. K. (2022). Eleanor Clarke Slagle Lecture—Finding our strengths: recognizing professional bias and interrogating systems. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 76, 7606150010. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2022.076603

Schaaf, R.C. & Mailloux, Z. (2015). Clinician’s guide for implementing Ayre’s sensory integration: Promoting participation for children with autism. American Occupational Therapy Association: Incorporated.

Walker, N. (2014a). Neuroqueer: The writings of Dr. Nick Walker. Neurodiversity: Some basic terms & definitions. https://neuroqueer.com/neurodiversity-terms-and-definitions/

Walker, N. (2014b). Neuroqueer: The writings of Dr. Nick Walker. Neurotypical psychotherapists & autistic clients. https://neuroqueer.com/neurotypical-psychotherapists-and-autistic-clients/

After many months of work the new Talking Mats sensory resource; Me and My Senses is reaching the final phase and registrations open on Friday 31st March for our launch seminar. This blog gives an overview of what’s in the resource and our guest blog to be published on Friday is a powerful story of professional and personal learning with ‘Me and my senses’ playing a pivotal role.

The resource will aim to enable children and young people who have speech, language and communication needs (SLCN) and sensory integration difficulties to have a voice in their therapy assessment, planning and intervention. To find out more about the funding and development for this project please read the earlier blog here. It is also aimed at supporting all practitioners, regardless of their level of sensory integration training, to gain an individual’s voice of their ‘lived’ sensory experiences, needs and challenges.

It is divided into the following topics:

- My Spaces & Things I Do

- My Senses 1: Proprioception & Interoception

- My Senses 2: Vestibular

- My Senses 3: Taste, Smell, Hearing, Seeing, Touch

Use of the resource may contribute to sensory integration evaluation but does not replace a full sensory integration assessment, however it may equally work as a stand alone-tool. We hope that professionals from healthcare,education, in both mainstream and specialist settings, as well as colleagues in social care will value this resource.

Talking Mats is hosting an online seminar to introduce the resource and we have 50 sets to give away for free to the first 50 people who register for the seminar and are already Talking Mats trained. Registrations open on Friday.

Walking Back to Happiness.

We may not be able to guarantee happiness but our friend and advocate, Karen Mellon is running a further training on our Foot Care resource and that is definitely something to sing about!

Developed late 2021 and launched in 2022 the Foundation Training with the Foot Care resource was so popular we are running it again. The resource was developed in collaboration with Karen and her team at NHS Fife Podiatry but it is aimed at anyone for whom footcare is part of their role. The College of Podiatry recently published figures on costs to the NHS in England and diabetic foot care alone cost £1 – £1.2billion per year. Supporting patients to communicate health issues around their feet is one step towards ensuring they access the right care at the right time.

Karen recently presented to the Allied Health Professional’s Dementia webinar describing the resource from development to practise. You can view the presentation here, and read her blog from 2021 here.

The training is delivered on Teams in 2 sessions – January 24th 2024 and February 21st. Both sessions run from 9.20am – 12.30pm and both must be attended. The cost is £210 and this includes a copy of the Foot Care resource.

Online training login

Online training login