We are now half way through our project, funded by The Health and Social Care ALLIANCE Scotland, whose overall aim is to empower people with a range of long term conditions, with and without additional communication difficulties, to self-manage their own health and well-being by using Digital Talking Mats.

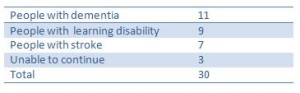

Participants

We have carried out all the initial visits and 16 follow-up visits and participants are sending in their completed mats, choosing whichever topics they want from the digital Health and Well-being resource. At the time of writing this blog we have received 137 completed mats.

We have received very positive feedback with many examples of how people are using the Digital Talking Mats to self-manage.

Here are 3 examples:

One participant with learning disability has diabetes. Through using the Digital Talking Mats she has stopped buying takeaways every night and is now buying M&S ‘Balanced for You’ meals. This is a huge step forward for her as she refused to discuss healthier eating before.

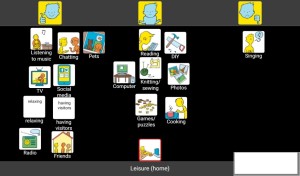

A man with early onset dementia has identified that he used to enjoy singing and has decided for the first time in his life to join a choir. This is not something that had come up in conversation before. Despite the diagnosis of dementia he has realised that he is still keen to try new things.

The wife of a man with severe aphasia said ‘This (Leisure away) has highlighted how few things he can do away from home. We discussed this but can’t see how we can change the situation.’ However at the second visit he used the same mat and indicated that he had been thinking about his mobility and was about to start swimming and a fitness class.

We already have an increased awareness of the meaning of self-management as we observe how participants are using the Digital Talking Mats to think about their situation, state their own views and share them with carers/support workers. We are also noticing that there is a shift in some relationships as the carers/support workers realise that the person with the long term conditions can make decisions and express their own views rather than having decisions made for them.

We are very grateful to Mary Walsh, Senior Speech and Language Therapist at St Mary’s Hospital in Dublin, for her Blog ;Does he like fairy cakes? ‘ It has been taken from her report on a project which looked at how speech and language therapists can facilitate the involvement of people with dementia to become more active participants in the decision making process around dysphagia management at the end stage of dementia. The project was funded by the Irish Hospice Foundation Changing Minds Programme

The project aims were:

- To improve person centred care in relation to residents’ food and drink preferences and dislikes

- To actively involve the residents of the dementia specific unit in the decision making process around their dysphagia (swallowing) management particularly at the end stage of their lives.

In order to find out the food and drink preferences and dislikes of the residents, the team carried out staff questionnaires and family questionnaires. They found that, although these were useful in getting a quick overview, there were a lot of unanswered questions.

The team also used Talking Mats and found it to be a powerful way to explore the residents’ food and drinks preferences and dislikes when used with suitable candidates. Participants appeared to really enjoy the experience including looking at pictures of the completed mats afterwards. This may be because they felt heard, that their views mattered and/or that they felt empowered. The information was important for current Dysphagia management, and also as an advanced directive in the documented evidence of the residents’ wishes in the recorded pictures of completed mats.

Brief Case Study: Does he like fairy cakes?

Talking Mats was used with a gentleman who may have been assumed to be unsuitable to use Talking Mats as he was assessed as having late stage dementia. However, this man engaged readily in the Talking Mats interview and appeared to be happy to have his views recorded. Also, there was a much higher level of correlation than variance with Talking Mats and both the staff questionnaire and the family questionnaire thus further indicating that he was a suitable candidate. ‘Fairy cakes’ was something that this resident reportedly liked in both the staff questionnaire and the family questionnaire. However, the gentleman indicated twice on Talking Mats that he disliked fairy cakes.

A number of actions are proposed in the report including :

- Continue to use Talking Mats as appropriate in the dementia specific residential unit and the rehabilitation wards of St. Mary’s Hospital.

- Inform the multi-disciplinary team of the merits of Talking Mats. This tool can also be used to explore other important issues for suitable residents/ patients on a case by case basis.

Conclusion:

It is essential to challenge our assumptions in our dealings with people with dementia. Truly person centred care takes time and patience where assumptions are challenged. Also, it is essential to listen to what residents tell us verbally, or through a supported communication system such as Talking Mats or non-verbally through tone of voice, facial expressions or gestures, and to act according to what is being communicated.

Delighted to introduce you to ‘The Communication Game’ : a board game for staff to improve their communication skills.

How we listen, talk and engage with people is fundamental to the quality and effectiveness of health and social care services. Although communication underpins everything we do in a work context, it can be a difficult topic for staff to talk easily about. Add to that the possibility of service users having an additional communication support need, through reasons like stroke, learning disability or dementia, then there is much potential for things to go awry and unfortunately, they often do. ‘Poor communication’ is cited as the most common cause of frustration in complaints about services.

The Communication Game was developed by Focus Games, NHS Education for Scotland (NES) and Talking Mats. It is a learning tool to help staff working in the health & social care sector increase their knowledge and skills around communication. The Communication Game is fun and easy to play. It can be played with or without a facilitator, and allows staff groups to have discussions and reflect on their communication skills. It allows them the chance to learn from each other. It will improve knowledge, but more importantly enable them to think about the small steps they can make to improve their interactions.

The project grew out of two previous projects funded by NES: Making Communication Even Better and Through a Different Door. In these projects, it was recognised that the experience of services for people with a communication support need is something of a lottery. For them, there was a considerable difference in the experience of interacting with a staff member who was empathetic and able adapt to their communication, to interacting with a member of staff who was struggling and unable to adapt their interaction. Training and understanding of inclusive communication practice is key. It has been a great privilege for Talking Mats to continue to support the work of the previous 2 projects and work with Focus Games Ltd to develop The Communication Game. Support during the development process from the Stroke Association Scotland, Capability Scotland, RCSLT, Scottish Care, Communication Forum, Queen Margaret University and NHS Ayrshire & Arran SLT Department have been invaluable, and we are very grateful; also to NHS Education for Scotland for their continued input and funding.

If you are working with staff in the health and social care sector, then this will be a great resource for you. You can get The Communication Game from the Focus Games online shop. It is guaranteed to promote laughter learning, and a touch of competitive team spirit. Most importantly, it will be a catalyst to help develop staff communication, making interactions better for people with communication support needs.

You can find out more about the game at www.communicationgame.co.uk

, and follow the game on Twitter on @Comm_Game.

Get your copy at www.focusgames.com.

This blog summarises a project we have completed providing Talking Mats training for families living with dementia. A key aspect of the work done by Talking Mats is to find ways to improve communication for families living with long term conditions. In particular dementia is a long term condition where deterioration in communication will eventually affect everyone. This makes it increasingly difficult to ensure that the person with dementia continues to be involved in decisions about their life.

We have completed a project funded by Health and Social Care ALLIANCE Scotland. Training in the use of Talking Mats was given to families living with dementia and staff who worked with these families. The Alliance Family Training final report highlights how this training helped people with dementia to communicate their views and be more involved in making decisions about their lives.

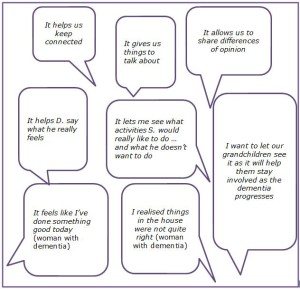

Families identified issues relating to self-management that they had not previously been aware of and new insights emerged as the following comments illustrate.(click on box to enlarge)

For some family members an important outcome was that Talking Mats helped them see that their spouse was satisfied with many aspects of his/her life. They found this very reassuring as many assumed that the person with dementia was frustrated and discontented.

The following is an example of how using Talking Mats helped with self-management.

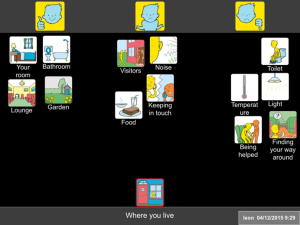

When using Talking Mats on the topic of Where you live, G explained that he found it difficult to find his way to the toilet in the night. As a result his wife bought special senior night lights to help him which solved their problem. As a result, night times improved for both of them.

For further examples and information read the full report here Alliance Family Training final report and for further information about Talking Mats Family training please contact info@talkingmats.com

Talking Mats considers both health and social aspects when it is used to include people in their care planning. Lots of interesting comments are made by course participants on the forum in our online training course. Annemarie, who works as an agency carer visiting clients in their own homes posted her thoughts about the social model of disability

Remembering the person behind the condition

In my experience, society is fixated on the medical model, the ‘what’s wrong’ approach. Whilst the medical model is clearly a valuable and required tool, it often leads to labels that individuals are then lumbered with, such as, ‘she has dementia’, ‘she is visually impaired’, ‘he’s deaf’ or has a ‘leaning disability’. Taking this approach overlooks the person behind the ‘condition’ and so can restrict inclusion. One example could be an individual with dementia being unable to make everyday choices about seemingly mundane issues such as what to wear that day. Using a medical model, a carer may be aware of the clients difficulties and make choices for them, whereas using the social model approach enables the carer to see beyond the condition and fully include the client, allowing them to be part of the decision making process for themselves. A second example could be a person with a communication disorder such as Asperger’s Syndrome. Access to work could be severely restricted using a medical model as the pragmatic manifestation of this condition may well exclude a person from seeking certain types of employment. Promoting the use of a social model would ensure work colleagues understood the possible limitations of the condition and ensure adequate support networks were in place. The social model attempts to embrace a person’s difference and raises awareness within society of individual needs that will facilitate inclusion into all aspects of life.

The WHO ICF -World Health Organisation International Classification Framework of Functioning, Disability and Health (2001, 2007b) aims to merge the medical and social model, encouraging professionals to think not only of the persons health condition and resulting impairment, but the impact this has on the persons participation and activities. It captures the full complexity of people’s lives, including environmental and social factors and can be applied over different cultures

The Talking Mats Health and Well- being resource is based on the WHO ICF and supports a person to reflect and express their view on various aspects of their lives. Using the Health and Well being resource supports workers to remember the person behind the condition.

We are delighted to have received funding from Life Changes Trust to work with Patient Opinion to help improve the access to their website by developing a Talking Mats to enable people to tell their stories.

Like Talking Mats, Patient Opinion is a Social Enterprise and has an excellent independent website https://www.patientopinion.org.uk/ that enables people to share their experiences of UK health services, good or bad. They then pass the stories to the right people so that they can learn from them.

The project we are working on is focusing on people with dementia but in the long run we hope that lots of people will benefit. It will bring our two innovative technologies together marrying the expertise of the Patient Opinion website with that of the Digital Talking Mats.

Our aim is that people affected by dementia can use their own voice to share their experiences and make real differences to relationships, services and culture, just as many others are already doing across health and care. We also hope that this work will empower others with communication or cognitive difficulties to share their experiences and be heard in an open and transparent way.

This ground breaking work is being funded and supported by Life Changes Trust, People Affected by Dementia programme. The Big Lottery funded programme is committed to working with people living with dementia and those who care for them, investing resources so that individuals are more able to face the challenges before them, and can exercise more choice and control in their own lives.

We expect the project to take 18 months to complete and have already run focus groups with people with dementia, family members and expert practitioners to plan the new symbols. We are now working with the technical experts to create the website interface which we will then pilot with people with dementia.

Watch this space for more updates…..

What are the top 10 blogs for using Talking Mats with adults? Over the years we have posted lots of blogs on different aspects of our framework . If you are working with adults with communication disability these blogs maybe particularly helpful

- Where is the best place to start using the Talking Mats health and well-being resource?

- A blog from Denmark which highlights the effectiveness of using Talking Mats with people with dementia

- Goal setting with a woman with Multiple sclerosis

- Using the app with someone with aphasia

- The development of a resource to help people with learning disability raise concerns

- How can Talking Mats support Capacity to make decisions

- Involving people in their decisions about eating and drinking

- Thoughts on using Talking Mats with people with dementia to explore mealtimes

- Using Talking Mats with someone with a learning disability and dementia

- Use in a rehab setting in South Africa

If you want to explore our resource and training more please visit our shop

We are very grateful to Anna Volkmer for sending us this blog, Lets Talk about Capacity…

She has just had an excellent book published – Dealing with Capacity and Other Legal Issues with Adults with Acquired Neurological Conditions http://www.jr-press.co.uk/dealing-capacity-legal-issues.html. In it she describes how AAC methods, including Talking Mats, can be used to support people in expressing their decisions.

Prior to 1959 people who were considered “non-compus mentis” were cared for under the “parens patriae” principle. Literally translated this meant that they were ‘parents of the country’ and decisions to protect them and their property were made by the Crown (the Lord Chancellor). These people were often described as “Chancery Lunatics”. In 1959 the “parens patriae” jurisdiction gave way to the Mental Health Act. This Act instructed that “the judge may, with respect to the property and affairs of a patient, do or secure the doing of all such things as appear necessary or expedient…for making provision for other persons or purposes for whom or which the patient might be expected to provide were he not mentally disordered” (section 102 (1)(c)). Unfortunately, this Act did not make adequate provision for non-financial decisions such as medical decisions. During this period it was case law that guided professionals in supporting their patients who lacked capacity in medical decision making. It was not until 2005 that the first Mental Capacity Act was given Royal Assent, accompanied by the Mental Capacity Act Code of Practice in 2007.

I returned to the UK from a 5-year stint working in Melbourne, Australia, just after the Mental Capacity Act had been published. Mental capacity was on the tip of everyone’s tongues and as the speech and language therapist working on a multi-disciplinary team I became an integral part of this process. Patients I was seeing, often people with primary progressive aphasia or other types of dementia, were asking about how to make future decisions. They and their families were keen to understand how the mental capacity act worked, how to prepare for the future and how to have their voices heard. On the other side of the coin I was working on an inpatient ward where staff were concerned about ensuring we were fully assessing the decision making capacity of people with cognitive and communication difficulties, often holding best interest discussion to plan for the future of these individuals. Many of these decisions related to dysphagia, but others related to accommodation and finances.

What concerned me was the lack of evidence available across the speech and language therapy arena in this area. There was little to none in terms of written research, let alone written advice or even examples of good practice tailored to speech and language therapy clinicians. As I asked around I found an enormous disparity in the services that speech and language therapy clinicians were providing across different trusts. I had previously written a book on dementia, and had included a chapter on assessments of decision-making. At this stage some of the only research related to communication and decision-making had come from Talking Mats. This had demonstrated that using the talking mats tools can support families and caregivers in conversations with their loved ones when discussing decisions to be made. They found that conversation enabled people in understanding, retaining and expressing themselves in decision-making discussions.

Following a particular stimulating discussion with the publishers at J&R press, they invited me to submit a book proposal on this topic. As I was developing this idea I found the topic of mental capacity was raised more and more often at study days and seminars I attended. At these study days I started linking in with more like minded speech and language therapists such as Mark Jayes, Hannah Luff and Claire Devereux. These were clinicians who all agreed on the diversity of our potential role in supporting our patients around mental capacity issues. These common interests enabled a collaboration. Our book is now published.

Through these connections I became aware of other work being done; Mark Jayes holds a NIHR doctoral fellowship award and is conducting research in the development of a communication and capacity assessment tool kit. Claire Devereux is the chair of the Southern Psychiatry of Old Age Clinical Excellence Network, together we have held a workshop with the clinical specialists where we developed a consensus document on role of the speech and language therapist in capacity assessment. This is to be published in Bulletin magazine later this year. Hannah Luff is a clinical lead speech and language therapist at South London and the Maudsley NHS Trust and is currently a member of the review panel looking at the NICE SCIE dementia guidelines.

The wonders and value of networking never ceases to delight, enthuse and inspire me! And you can purchase our book at the following website (there is currently a discount rate until 21st February):

http://www.jr-press.co.uk/dealing-capacity-legal-issues.html

You can follow me on my blog https://annavolkmersbigphdadventure.wordpress.com/ or on twitter @volkmer_anna

This is the second of Kristine Pedersen’s projects using Talking Mats as a tool to support people with dementia.

Care workers at two residential care homes in Denmark were taught how to use the Talking Mats framework and how to incorporate the method into planning daily activities for people with dementia.

The care workers gave positive feedback in regard to using Talking Mats:

- Using the Talking Mat framework provides important knowledge about communicative difficulties of the person with dementia

- Talking Mats helps people to understand their options and thereby motivates to social activities, eating, physical exercise, etc.

- Talking Mats increases the possibility of active participation in caregiving plans

- Talking Mats enhances the joy of work, when I know how I can give the right care

- The Talking Mats conversations support a closer relation between elderly and care giver

This project and the one described in the previous blog, gave the opportunity to explore the Talking Mat framework in use and how the framework can support the communication of people with dementia. Very importantly, due to the adoption of Talking Mats and its extension in Denmark, the projects gave a lot of Danish examples. The projects also gave important information about how to implement the tool in care homes for people with dementia within a Danish setting.

‘We are very grateful to the Directors, Dr Joan Murphy and Lois Cameron and everyone on the team at the Talking Mats Centre who developed the framework and who continue to increase knowledge of Talking Mats through research and education. It is a very helpful tool for many people and supports and enables more people to have their views seen and heard’

And we are grateful to Kristine for sharing her projects with us.

We are very grateful to Kristine Pedersen from Kommunikationscentret in Denmark for sharing the findings of 2 projects with us. The first project found Talking Mats was effective in supporting communication for people who have dementia when compared with both unstructured and structured conversations.

‘t is important to know how to give people with dementia the right support’

At Kommunikationscentret in Hillerød (Denmark), we have been using the Talking Mats framework since our first trainer was accredited at the Talking Mats Centre, University of Stirling in 2010. We have been using Talking Mats with both children and adults across a range of communication difficulties e.g. caused by Aphasia, Cerebral Palsy, Downs Syndrome, learning difficulties etc. Inspired by the important research project by Dr. Joan Murphy and others ‘Decision making with people with dementia’ (2010), our next step was to gain our own experience within the framework specifically aimed towards people with dementia.

As in the rest of the world, the number of people in Denmark with dementia is increasing. Symptoms of dementia vary from person to person but many of the symptoms are related to communication: Difficulties finding words, using familiar words repeatedly, losing track in conversation, difficulties in focusing and paying attention etc. The growing dependence of the person with dementia on a caregiver makes communication essential to express wishes and needs. Therefore, it makes sense to look at the consequences of the illness (dementia) within the perspective of communication and how family members and professionals around the person with dementia can support communication using AAC.

The purpose of the first project was to compare the communication in conversations about views on I) Daily activities and II) The importance of information, using three different communication methods. The methods were: 1) unstructured conversation 2) structured conversation 3) the Talking Mats framework. The project involved 6 participants having early to moderate stage dementia, all living in residential care homes.

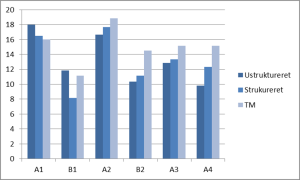

Like the study ‘Decision making with people with dementia’ (2010), the report concludes that the Talking Mats method was associated with better communication for the majority of the participants. The Talking Mats framework was found especially helpful regarding the participant’s ability to understand subject and question of the conversation, the participant’s ability to reflect, and the participant’s ability to make themselves understood. The graph below shows that only one participant (A1) did not benefit from the visual method. She had poor eyesight, which strongly indicates that visual support compensates the difficulties that people with dementia have.

The report also concludes that the Talking Mats framework increases the interviewer’s ability to detect and compensate for some of the communication difficulties. Finally, it seemed that several of the participants have been able to learn how to use Talking Mats in the process.

The photo underneath shows a Talking Mat conversation from the project. This Talking Mat gives an insight into how this person feels about what information is important to her, and what isn’t. It is in some way a difficult and abstract question, but most of the participants managed to both understand, reflect and answer the question when we used the Talking Mats framework.

Important information to this participant is information about new neighbours, the menu at the residential care home, economy etc. Less important is news about the Danish royal family, technology, getting older etc. Politics is definitely not important to her.

Online training login

Online training login